Leukopenia (from Greek, Modern (leukos), meaning ‘white’, and (penia), meaning ‘deficiency’) is a decrease in the number of white blood cells (leukocytes) found in the blood, which places individuals at increased risk of infection.

Neutropenia, a subtype of leukopenia, refers to a decrease in the number of circulating neutrophil granulocytes, the most abundant white blood cells. The terms leukopenia and neutropenia may occasionally be used interchangeably, as the neutrophil count is the most important indicator of infection risk. This should not be confused with agranulocytosis.

Low white cell count may be due to acute viral infections, such as a cold or influenza. It has been associated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, myelofibrosis, aplastic anemia (failure of white cell, red cell and platelet production), stem cell transplant, bone marrow transplant, HIV, AIDS, and steroid use.

Other causes of low white blood cell count include systemic lupus erythematosus, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, some types of cancer, typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, dengue, rickettsial infections, enlargement of the spleen, folate deficiencies, psittacosis, sepsis, Sjögren’s syndrome and Lyme disease. It has also been shown to be caused by deficiency in certain minerals, such as copper and zinc.

Pseudoleukopenia can develop upon the onset of infection. The leukocytes (primarily neutrophils, responding to injury first) start migrating toward the site of infection, where they can be scanned. Their migration causes bone marrow to produce more WBCs to combat infection as well as to restore the leukocytes in circulation, but as the blood sample is taken upon the onset of infection, it contains low amount of WBCs, which is why it is termed “pseudoleukopenia”.

Conventional Pharmaceuticals can alter the number and function of white blood cells

Medications that can cause leukopenia include clozapine, an antipsychotic medication with a rare adverse effect leading to the total absence of all granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils).

The antidepressant and smoking addiction treatment drug bupropion HCl (Wellbutrin) can also cause leukopenia with long-term use.

Minocycline, a commonly prescribed antibiotic, is another drug known to cause leukopenia. There are also reports of leukopenia caused by divalproex sodium or valproic acid (Depakote), a drug used for epilepsy (seizures), mania (with bipolar disorder) and migraine.

The anticonvulsant drug, lamotrigine, has been associated with a decrease in white blood cell count.[1]

The FDA monograph for metronidazole states that this medication can also cause leukopenia, and the prescriber information suggests a complete blood count, including differential cell count, before and after, in particular, high-dose therapy.

Immunosuppressive drugs, such as sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, ciclosporin, leflunomide and TNF inhibitors, have leukopenia as a known complication.[2]

Interferons used to treat multiple sclerosis, such as interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b, can also cause leukopenia.

Chemotherapy targets cells that grow rapidly, such as tumors, but can also affect white blood cells, because they are characterized by bone marrow as rapid growing.[3]

A common side effect of cancer treatment is neutropenia, the lowering of neutrophils (a specific type of white blood cell).[4]

Decreased white blood cell count may be present in cases of arsenic toxicity.[5] It’s well known among holistic healers and serious scientists that arsenic is the first most prevalent cancer-causing chemical in the US, including in its “potable” whater supply and rice. (Source)

Assessment

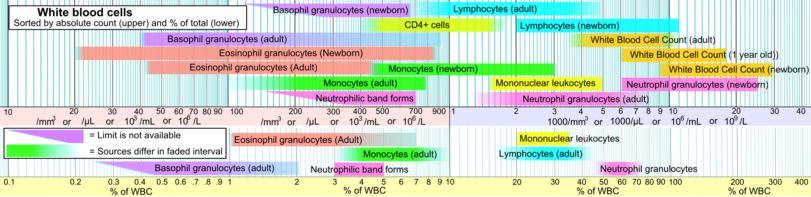

Leukopenia can be identified with a complete blood count.[6] Below are blood reference ranges for various types leucocytes/WBCs.[7] The 2.5 percentile (right limits in intervals in image, showing 95% prediction intervals) is a common limit for defining leukocytosis.

References

- Nicholson, R J; Kelly, K P; Grant, I S (25 February 1995). “Leucopenia associated with lamotrigine”. BMJ. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- “Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia induced by etanercept: two case reports and literature review”. 52 (1): 110–2.

- “What causes low blood cell counts?”. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- “Managing a Low White Blood Cell Count (Neutropenia)”. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- Xu, Yuanyuan; Wang, Yi; Zheng, Quanmei; Li, Bing; Li, Xin; Jin, Yaping; Lv, Xiuqiang; Qu, Guang; Sun, Guifan (1 June 2008). “Clinical Manifestations and Arsenic Methylation after a Rare Subacute Arsenic Poisoning Accident”. Toxicological Sciences. 103 (2): 278–284. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn041. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via toxsci.oxfordjournals.org.

- “What an Abnormal White Blood Cell Count Means”. about.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Specific references are found in article Reference ranges for blood tests#White blood cells 2.