In Conventional Oncology, bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder.[1] It is a disease in which cells grow abnormally and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body.[7][8]

Bladder Cancer is one of the most commonly occurring forms of cancer in the United States today. Over 75% of those diagnosed will be men, making bladder cancer the fourth most common cancer to affect the male population.

Bladder cancer can be difficult to diagnose, as early symptoms can often be attributed to other conditions such as kidney stones or bladder infections.

As soon as bladder cancer is detected, the patient should take care so as to delay the tumor progression. It is advisable to maintain a proper diet and live holistically throughout the course of the disease.

The future patient must act fast as these cancers tend to be fast-growing: Below, the typical conventional approach.

“Bladder tumors almost always arise from the shiny bladder lining. The cells grow abnormally fast causing a tumor to sprout up from the flat lining into a growth projecting into the interior of the bladder cavity. In general, tumors at this stage are not life-threatening. They usually do not cause any symptoms and remain unnoticed until an episode of bleeding into the urine. After an episode of bleeding into the urine, the patient should undergo an evaluation by a urologist. The urologist is usually called upon to look into the bladder with a cystoscope (a telescope that can be inserted into the bladder). The urologist may also order various types of X-ray studies. (…) After diagnosis, the patient usually undergoes biopsy and/or removal of the tumor. This procedure, called “transurethral resection of bladder tumor,” is accomplished using cystoscopes…”. (Source)

Symptoms

As noted, symptoms include blood in the urine (hematuria), pain with urination, the urge to urinate but an inability to urinate, cloudiness in the urine, An increase in the frequency of urination, urinary incontinence and low back pain.[1]

Major Risk Factors

Risk factors for bladder cancer include, but are not limited to family history, prior radiation therapy, frequent bladder infections, and exposure to certain chemicals.[1] The most common type is transitional cell carcinoma.[3] Other types include squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.[3]

But as we suggested, just about all cancers will respond to the HIP holistic protocol because all cancer cells are all wired in a similar way. It is those wired pathways that the HIP protocol addresses.

A number of risk factors are involved. Apart from genetic and hereditary factors, these factors include infection, parasite, smoking, a high-fat or rich diet, exposure to specific chemicals, dyes or drugs, and people who work in the aluminum, rubber or leather industry.

Other Risk Factors

Are over the age of 40, since your risk increases as you get older. About 9 out of 10 people with bladder cancer are older than 55. Are males, who develop bladder cancer much more often than females do. Have had cancer in the past, especially cancer affecting the urinary tract. Smoke or use tobacco products. Cigarette smoking is considered one of the most important causes of bladder cancer since it causes toxins to travel to the kidneys and into the urine where they are exposed to the bladder lining.

Are Caucasian/whites. People who are white have about twice the chance of developing bladder cancer as African Americans and Hispanics.

Are exposed to certain chemicals and toxins that can damage your kidneys, such as due to exposure at work or through environmental pollution. Chemicals linked to bladder cancer include arsenic, benzidine and beta-naphthylamine and chemicals used in the manufacture of dyes, rubber, leather, textiles and paint products. According to the American Cancer Society,

“..workers with an increased risk of developing bladder cancer include painters, machinists, printers, hairdressers, and truck drivers (likely because of exposure to diesel fumes).” (Source)

Arsenic is often found in water, according to one source, up to 20 percent of American potable water has arsenic that exceeds tolerated limits. Same with American rice. (Source)

Have a history of chronic bladder infections or irritation of the lining of the bladder, such as from long-term use of a urinary catheter. The bladder can become irritated from urinary tract infections, kidney stones or prostate infection. (Source)

“These data support a casual relationship between S. haematobium infection and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder” (Source)

Parasitic infection called schistosomiasis (also known as bilharziasis), which mainly affects people living or visiting Africa and the Middle East, can also increase bladder cancer risk.

Have a family history of cancer, especially of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, also called Lynch syndrome. People with a genetic mutation of the retinoblastoma (RB1) gene, or Cowden disease, are also at an increased risk. Have a rare birth defect that affects the urinary tract and bladder, including those called exstrophy or urachus. Have taken diabetes medication called pioglitazone (Actos) for more than one year. (Source)

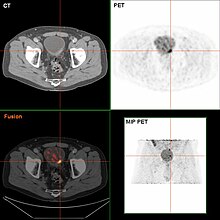

Bladder tumor in FDG PET due to the high physiological FDG-concentration in the bladder, furosemide was supplied together with 200 MBq FDG. The uptake cranial to the lesion is a physiological uptake in the colon.

Causes of Bladder Cancer

Conventional Oncology experts claim that they dont know what the causes of bladder cancer are, yet, as we just saw, there exists multiple causes, in particular with regard to toxemia and infections. As a consequence, it is safe to assert that toxcemia is a major cause of bladder cancer. Thus, any protocol like conventional oncology that side-steps detoxification is necessarily flawed.

Conventional Diagnosis is typically by cystoscopy with tissue biopsies.[4]

Currently, in conventional oncology the best and most practiced diagnosis of the state of the bladder is by way of cystoscopy, which is a procedure in which a flexible tube bearing a camera and various instruments is introduced into the bladder through the urethra. The procedure allows for a visual inspection of the bladder, for minor remedial work to be undertaken and for samples of suspicious lesions to be taken for a biopsy.

Urine cytology can be obtained in voided urine or at the time of the cystoscopy (“bladder washing”). Cytology is not very sensitive (a negative result cannot reliably exclude bladder cancer).[19] There are newer non-invasive urine bound markers available as aids in the diagnosis of bladder cancer, including human complement factor H-related protein, high-molecular-weight carcinoembryonic antigen, and nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22).[20] NMP22 is also available as a prescription home test. Other non-invasive urine based tests include the CertNDx Bladder Cancer Assay, which combines FGFR3 mutation detection with protein and DNA methylation markers to detect cancers across stage and grade, UroVysion, and Cxbladder.

The diagnosis of bladder cancer can also be done with a Hexvix/Cysview guided fluorescence cystoscopy (blue light cystoscopy, Photodynamic diagnosis, see ACRI’s file), as an adjunct to conventional white-light cystoscopy. This procedure improves the detection of bladder cancer and reduces the rate of early tumor recurrence, compared with white light cystoscopy alone. Cysview cystoscopy detects more cancer and reduces recurrence. Cysview is marketed in Europe under the brand name Hexvix.[21][22][23][24]

However, visual detection in any form listed above, is not sufficient for establishing pathological classification, cell type or the stage of the present tumor. A so-called cold cup biopsy during an ordinary cystoscopy (rigid or flexible) will not be sufficient for pathological staging either. Hence, a visual detection needs to be followed by transurethral surgery. The procedure is called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). Further, bimanual examination should be carried out before and after the TURBT to assess whether there is a palpable mass or if the tumour is fixed (“tethered”) to the pelvic wall. The pathological classification obtained by the TURBT-procedure, is of fundamental importance for making the appropriate choice of ensuing treatment and/or follow-up routines.[25]

Histopathology of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Transurethral biopsy. H&E stain.

Typology

95% of bladder cancers are transitional cell carcinoma. The other 5% are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, small cell carcinoma, and secondary deposits from cancers elsewhere in the body.[26] Carcinoma in situ (CIS) invariably consists of cytologically high-grade tumour cells.

Conventional Bladder cancer treatments

Treating bladder cancer will vary from patient to patient depending on the size and stage of the tumor. Treatments may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, intravesical therapy or a combination of two treatments.

Surgery

Bladder cancer surgery is known as a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (or TURBT). This procedure is performed by placing a small tube-shaped instrument up the urethra to remove and scrape away tumor cells found in the inner lining of the bladder. A TURBT does not require a large incision across the abdomen, and the patient will not have a scar following the surgery.

If the bladder cancer is more advanced, a cystectomy surgery may be performed. During a partial cystectomy, a surgeon removes a portion of the bladder, while a radical cystectomy removes the entire bladder. If the entire bladder is removed, the patient will require a subsequent reconstructive surgery in order to implement a system to store and excrete urine. Most bladder cancer patients do not require a cystectomy surgery. Radical cystectomy in the US in 2017 was around 40,000 dollars. (Source)

Intravesical therapy

This form of bladder cancer treatment involves placing a liquid drug directly into the bladder by way of a catheter. This offers targeted treatment with little chance of damaging healthy cells. Intravesical therapy is typically reserved for early stage cases as the liquid medicine can only be distributed within the inner lining of the bladder.

Chemotherapy

Intravesical chemotherapy includes the procedure mentioned above used with chemotherapy medicine. Another form of chemotherapy for bladder cancer is systemic chemotherapy. This form of chemotherapy is delivered either in pill or through an IV, both of which deliver the medicine to the blood stream to treat the bladder cancer.

Radiation

Radiation involves applying radiation waves to destroy the cancer cells. External beam radiation is the most common form of radiation used to treat bladder cancer. The procedure usually requires daily sessions for weeks before treatment is complete.

Following any form of bladder cancer treatment, a physician will monitor the patient every three to six months to determine that the cancer cells have or have not returned.

Discussion

Convention Oncology prefers invasive biopsies and treatments. Because of the dangers and risks of tissue (excisional) biopsies, including, but not limited to the risk of promoting metastases, the ACR Institute prefers CTC blood tests (sometimes called “liquid biopsies) as well as other tests, including the muscle testing conventional oncologists call quakery, just like with detoxification, the NIH also calls that quakery, unproven, (Source) when the preponderance of the credible evidence is overwhelming that detoxification is a proven and useful approach for all chronic diseases, including bladder cancer.

Text under construction

To learn about the holistic and innovative techniques that can help to better control and reverse this health condition, including, but not limited to BCG, consider scheduling a consult.

References

- “Bladder Cancer Treatment”. National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- “Cancer of the Urinary Bladder – Cancer Stat Facts”. seer.cancer.gov. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- “Bladder Cancer”. National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- “Bladder Cancer Treatment”. National Cancer Institute. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). “Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015″. Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). “Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015″. Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903.

- ^ “Cancer Fact sheet N°297″. World Health Organization. February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ “Defining Cancer”. National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ^ Avellino, Gabriella J.; Bose, Sanchita; Wang, David S. (2016-06-01). “Diagnosis and Management of Hematuria”. Surgical Clinics of North America. 96 (3): 503–515. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2016.02.007.

- ^ Zeegers MP; Tan, FE; Dorant, E; Van Den Brandt, PA (2000). “The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies”. Cancer. 89 (3): 630–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 10931463.

- Osch, Frits H. M. van; Jochems, Sylvia H. J.; Schooten, Frederik-Jan van; Bryan, Richard T.; Zeegers, Maurice P. (2016-04-20). “Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies”. International Journal of Epidemiology. 45 (3): 857–870. doi:10.1093/ije/dyw044. ISSN 0300-5771.

- ^ Lee, PN; Thornton, AJ; Hamling, JS (October 2016). “Epidemiological evidence on environmental tobacco smoke and cancers other than lung or breast”. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 80: 134–63. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.06.012.

- ^ Reulen RC, Zeegers MP (September 2008). “A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation”. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. Supplementum. 42 (218): 64–78. doi:10.1080/03008880802325192. .

- ^ Guha, N; Steenland, NK; Merletti, F; Altieri, A; Cogliano, V; Straif, K (August 2010). “Bladder cancer risk in painters: a meta-analysis”. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 67 (8): 568–73. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.051565.

- ^ Sun, Jiang-Wei; Zhao, Long-Gang; Yang, Yang; Ma, Xiao; Wang, Ying-Ying; Xiang, Yong-Bing (24 March 2015). “Obesity and Risk of Bladder Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 15 Cohort Studies”. PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0119313. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019313S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119313. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4372289.

- ^ Al-Zalabani, AbdulmohsenH.; Stewart, KellyF.J.; Wesselius, Anke; Schols, AnnemieM.W.J.; Zeegers, MauriceP. (2016-03-21). “Modifiable risk factors for the prevention of bladder cancer: a systematic review of meta-analyses”. European Journal of Epidemiology. 31 (9): 811–851. doi:10.1007/s10654-016-0138-6. ISSN 0393-2990. PMC 5010611.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 109800

- ^ Lotan, Y.; Roehrborn, C. G. (2003). “Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: Results of a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses”. Urology. 61 (1): 109–118, discussion 118. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02136-2.

- ^ Shariat; Karam, JA; Lotan, Y; Karakiewizc, PI; et al. (2008). “Critical Evaluation of Urinary Markers for Bladder Cancer Detection and Monitoring”. Reviews in Urology. 10 (2): 120–135.

- ^ “Hexvix”. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013.

- ^ “Photocure—Cysview Hexaminolevulinate (HCL)”. Cysview.net. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2011. Fluorescence-guided transurethral resection of bladder tumours reduces bladder tumour recurrence due to less residual tumour tissue in Ta/T1 patients

- ^ “Hexvix guided fluorescence cystoscopy reduces recurrence in patients”. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- “European Association of Urology (EAU)—Guidelines—Online Guidelines”. Uroweb.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ “Types of Bladder Cancer: TCC & Other Variants | CTCA”. CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.